NASA: 30-day demo isn’t a pivot—long-duration missions still anchor commercial space station plans

A short demo, not a strategy shift

A 30-day mission sounds like a big change. NASA says it isn’t. The agency clarified that a new month-long demonstration in its updated roadmap for commercial stations is a test run, not a new norm. The long-term plan still centers on extended stays in low Earth orbit—missions that deliver deeper science, more reliable operations, and a steady human presence.

This matters because the International Space Station won’t last forever. The U.S. aims to keep the ISS flying through the end of the decade, then retire it in a controlled deorbit. To avoid a gap, NASA is steering industry to build and operate the next generation of platforms while NASA becomes one paying customer among many. That transition only works if those new stations can support long stays with consistent crew time and robust life-support systems.

Short missions do have a role. NASA’s plan allows early demonstration visits to shake down new hardware, test procedures, and validate emergency protocols. Think of them as shakedown cruises—useful for proving docking systems, power and thermal control, and crew habitability before stretching to months-long campaigns. But the end state, NASA stresses, is not a string of brief flybys. It’s months-on-orbit work that looks and feels like what the ISS does today, just on commercial platforms.

NASA’s private astronaut mission program—launched in 2019—has been a key proving ground. These flights use the ISS as a destination for research, outreach, and commercial work. They’ve varied in length, from week-long stays to multi-week visits. Axiom Mission 4, targeting June 2025, is slated for roughly 18 days in orbit, following prior missions that ranged from 8 to 18 days. Each flight helps teach industry how to plan, train, operate, and recover crews—skills they’ll need when their own stations come online.

The point of those shorter visits isn’t to redefine NASA’s cadence. It’s to sample demand, sharpen operations, and build confidence ahead of the next phase: routine, extended stays on privately owned platforms. NASA is clear—long-duration missions are the backbone of its low Earth orbit strategy because they deliver the most science per dollar and because they keep crewed spaceflight skills sharp.

Why long stays still matter

Long-duration missions unlock research you simply can’t do on quick trips. Human physiology studies—bone density, muscle loss, immune response, and cognition—need months of data. Technology demonstrations—closed-loop life support, recycling systems, radiation monitoring, robotics, and in-space manufacturing—need time to cycle through test points and failures. Manufacturing experiments for pharmaceuticals and advanced materials benefit from steady access to microgravity and predictable crew time.

There’s also the operational side. Running a station for months requires reliable cargo and crew logistics, detailed maintenance cycles, and robust fault response. Those are the lessons that keep spaceflight safe and affordable. NASA has spent decades building that playbook on the ISS, and it wants commercial partners to carry it forward.

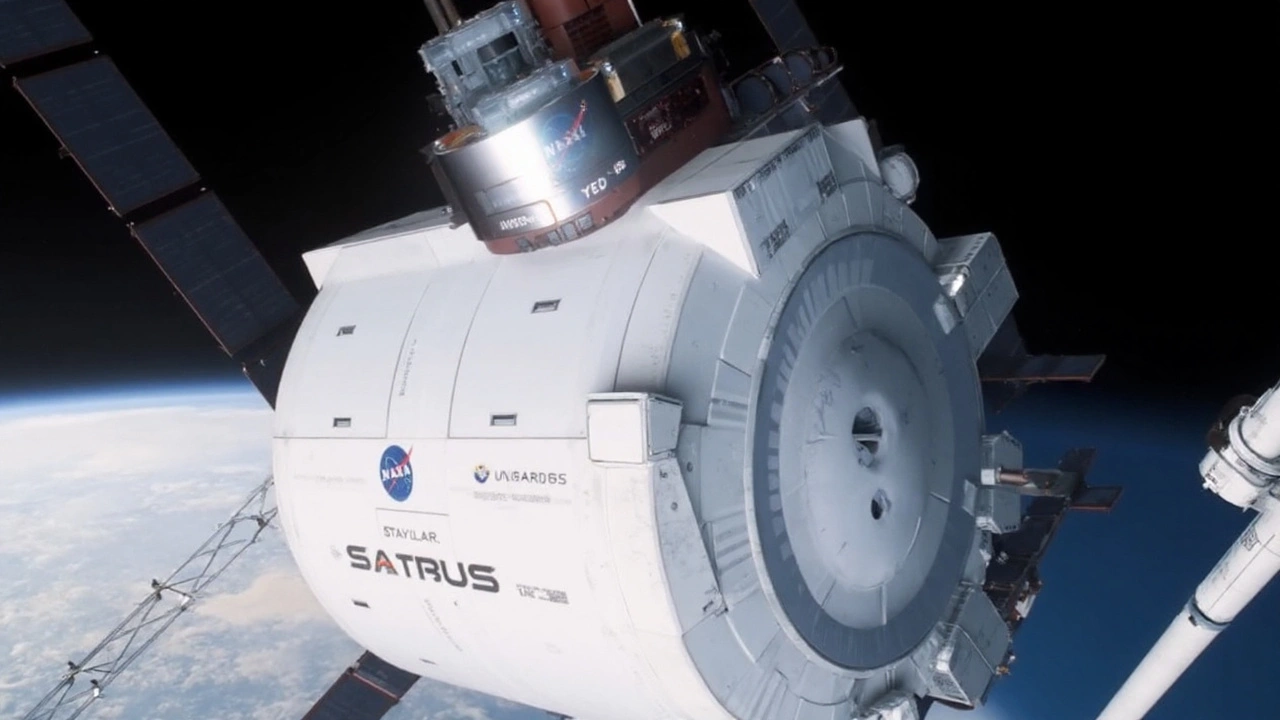

Who’s in the game? Multiple teams are advancing designs for commercial space stations. Industry concepts include free-flyers that can host visiting vehicles and scaled modules that build up over time. Axiom Space is taking a staged approach, starting with modules that attach to the ISS before forming an independent station. Other teams are designing new free-flying platforms from scratch. NASA’s early investments help mature these designs, but the goal is a market where non-NASA customers—research labs, national space agencies, pharma and materials firms, in-space manufacturing startups, and even media projects—buy services alongside NASA.

That market needs more than cool renderings. It needs standards, certifications, and realistic schedules. Early demo missions—like the 30-day checkout NASA referenced—are intended to prove readiness for crewed operations: safe docking and undocking, continuous power and thermal management, dependable environmental control, and clear emergency procedures. Once those boxes are checked, operators can scale to months-long campaigns, add more crew, and open more lab time.

NASA’s message also reflects a hard-learned lesson from the shuttle retirement: avoid gaps. The agency wants overlap—ISS operations continuing while the first commercial stations begin crewed missions. That overlap reduces risk, gives crews and ground teams time to learn new systems, and keeps research flowing without interruption. The alternative—shutting down the ISS before replacements are ready—would stall microgravity science and cede ground to competitors.

Funding and policy still matter. NASA’s commercial LEO efforts depend on steady budgets and clear milestones. Certification standards have to be tough enough to keep crews safe but lean enough to avoid needless delays. And the business model has to work: operators need anchor demand from NASA and a growing mix of non-NASA customers to keep costs in check.

Private astronaut missions will keep pulling double duty. They test hardware and operations while also proving out the market—how much high-net-worth demand is there, which national space agencies want seats, and what kinds of research customers are willing to pay for. Recent missions have shown researchers can fly meaningful payloads on short stays, but NASA’s own science portfolio—especially human health and long-horizon tech—relies on longer campaigns.

Here’s how the next few years likely unfold:

- ISS remains the primary U.S. platform for human spaceflight in low Earth orbit this decade, with a controlled deorbit planned at the end of its life.

- Commercial station teams complete design milestones, ground tests, and uncrewed demos, followed by short crewed checkouts.

- NASA continues private astronaut missions to refine training, timelines, payload integration, and post-flight analysis.

- Once platforms are ready, NASA shifts to extended-duration crew rotations, preserving continuous human presence in orbit.

That’s the throughline behind NASA’s clarification. A 30-day demo helps operators prove they can fly safely and reliably. But the destination is long-duration missions that keep labs busy, crews trained, and the United States firmly in the lead in low Earth orbit. Short visits will still happen—for business development, for quick-turn experiments, for outreach—but the main act is measured in months, not days.